How Hoosier came to represent Indiana University

From Hillbilly to Higher Education:

How Hoosier came to represent Indiana University

A headline in the Indiana Daily Student (IDS) from February 9th, 2017, reads, “Hoosiers battle Boilermakers in 117th Season.” In passing, the statement is unremarkable: readers understand that it is referring to an upcoming game between Indiana University and Purdue University; the next episode in a decades-long rivalry between two major Indiana universities. However, closer examination of the headline reveals that an interesting contradiction: If both schools are from Indiana, why is only one of them known as the Hoosiers? Although Hoosier has been used to describe people from Indiana for nearly as long as the state has existed, in 1923, Indiana University began using the nickname Scrapping Hoosiers for their football team, and, since then, has claimed Hoosier as their mascot and official team name. While other schools in Indiana developed identities of their own, Indiana University stuck with the term Hoosier, creating an interesting distinction between people from Indiana and people from Indiana University. It is difficult to trace when exactly change took place, so digital mapping and text analysis are necessary to help understand the transformation.

The first written references of Hoosiercome from the early 1800s, around the same time that Indiana became a state. Although use of the word Hoosier was initialy sparse, the phrase was adopted into common use throughout the nineteenth century. The most famous and wide-spread early use occurred in a poem titled “The Hoosier’s Nest,” written in 1830 by John Finley and published in a newspaper from Richmond, Indiana. Additionally, in 1866, Finley published a second version of the poem in a collected volume of his writings. The poem was very well received, and established many of the basic images which are still associated with the Hoosiers today: hard-working, hardy, hospitable, and proud. For example, the poem reads:

Who settles here to till the soil, And with intentions just and good, acquires and ample livelihood: He is… the bone and sinew of the State.*

Finely also mentions hospitality:

I’m told, in riding somewhere West, a stranger found a Hoosier’s nest The Hoosier met him at the door… Invited shortly to partake of venison, milk and johnny cake, the stranger made a hearty meal.

He describes a typical homey, Hoosier cabin in the country:

One side was lined with divers garments, The other spread with skins of varmints; Dried pumpkins overhead were strung, Where venison hams in plenty hung; Two rifles placed above the door; Three dogs lay stretched upon the floor— In short, the domicile was rife/ with specimens of Hoosier life.

Additionally, Finley creates a distinction between a life spent in this hardy Hoosier-way, and a life spent in a city, receiving higher education. He makes it clear that his poem is not intended for the intellectual elite, but rather, the common laborers. The first lines of his poem read:

Untaught the language of the schools, Nor versed in scientific rules, The humble bard may not presume The literati to ilume; … Contented if his strains may pass The ordeal of the common mass And raise an anti-critic smile The brow of labor to beguile.

He also suggests that Easterners judge Hoosiers, describing:

Our hardy yeomanry can smile At tourists of ‘the sea-girt isle… A strutting fop, who boasts, of knowledge Acquired at some far eastern college Expects to take us by surprise… Not thus the honest son of toil.

Finley was not the only person to make a distinction between Hoosiers and educated Easterners, more stereotypically known as Yankees. In fact, although Finley speaks of Hoosiers with pride, the word was no doubt used derogatively by those outside of Indiana to mean something akin to today’s hillbilly, redneck, or hick, in contrast to educated Yankees. In the mid-nineteenth century outside of Indiana, humorous ‘Hoosier stories’ were frequently published in periodicals, and, although other Midwestern states were featured, Indiana was by far the most common setting. A scholar from the mid-twentieth century describes:

Sometimes direct, sometimes vague and oblique, often coarse, insipid and pointless, Hoosier stories appear to be a journalistic innovation intended to ridicule a type of culture which was antithetical to that of the Yankees….[In the stories]…the Hoosier might be ‘green to the highest degree of verdancy, ignorant, and awkward, and attired in the acme of flashy bad taste’…[but] he was likely to prove ‘quite as sharp as city folks.’…After making fun of the Hoosier’s appearance…the narrator often permitted his rustic principle to come off victorious by means of a crashing verbal broadside….Along with the extreme rurality and illiteracy imputed to Indiana, the unwary reader of mid-century was encouraged to believe that barter economy, wildcat finances and bank notes, disorderly and ignorant legislators, unenlightened public policy, and easy divorce chronically emphasized in the states’ lapses from social orthodoxy.

Although the Hoosier stereotype lost some of its popularity in popular culture as railroads developed in Indiana and provided for better communication and connection with the East and West Coasts, it is clear that contrasting definitions of Hoosier existed throughout the nineteenth century. By 1848, Hoosier was defined in Bartlett’s Dictionary of Americanisms as “nickname given at the West to natives of Indiana.” However, an author describing her visit to Indiana in 1876 notes:

I thought I should find Hoosiers in Indiana, and rough uncultured Hawk-eyes in Iowa; but somehow, I am woefully disappointed, for they all seem to be men and women everywhere…I almost believe I have seen one Hoosier though…who is kind of cold-colored, a sort of drab that takes in hair, eyes, face, and dress, and baptizes each with shivery and melancholy bluish tint.

Although the author was impressed with Indiana’s civility, rather than assuming that her definition of Hoosiers is wrong, she claims she has not really met a Hoosier.

By the turn of the twentieth century, Hoosier was a well-accepted moniker for Indiana, although no formal definition for what it exactly meant to be a Hoosier was ever established. Several baseball teams in Indianapolis went by the Hoosiers, including the Indianapolis Hoosiers of the National League Baseball Club from 1887-89 and the Indianapolis Hoosiers Federal League in 1914. In the Indiana Daily Student, Indianapolis was called the Hoosier Capital, and Crawfordsville was called the Hoosier Athens. James Whitcomb Riley was called the Hoosier poet, and Hoosier Clubs began to be formed around the country. Indiana University’s 1915 Arbutus was dedicated to the “Hoosier Spirit.” Hoosier was also used in reference to people from Indiana, such as a Hoosier crowds, or two Hoosier teams playing each other.

At the same time that the word Hoosier was gaining recognition, the state of Indiana experienced a rise in institutions of higher education. In 1805, Jefferson Academy, which later became Vincennes University was founded. Indiana University, then called the State Seminary or the Indiana College, followed in 1820. More colleges sprung up in Indiana soon after: Wabash College was founded in 1832; Franklin College was founded in 1834 as the Indiana Manual Labor Institute; Indiana Asbury University, today called DePauw, was founded in 1837; Notre Dame University was founded in 1842; Earlham was founded in 1847; North Western Christian University, which later became Butler University, was founded in 1855; the Indiana State Normal School, today called Indiana State University, was founded in 1865; and finally, Purdue was founded in 1869.

The many colleges of Indiana competed with each other to be seen as the ‘true’ Indiana school. This was done in many ways, but by the end of the nineteenth century, sports—in particular football—was used to gain prestige and show the strength of the school’s spirit. Indiana’s first intercollegiate game occurred in 1884 between Butler and DePauw Universities. In 1887, Purdue and Indiana University both formed football teams, playing each other for the first time in 1891. By 1925, this Purdue-Indiana rivalry was formalized with the creation of the Old Oaken Bucket trophy and the annual football match continues to be played to this day.

Many college teams adopted names and nicknames early in their teams’ histories, which created a shared identity for the students. Purdue earned the name Boilermakers after a match in 1892 against Wabash, when the name was used by student reporters in the Wabash College newspapers. In 1904, Wabash College dubbed themselves the Little Giants, a nickname which they still use today. Franklin College students were the Fighting Baptists, which was changed in 1929 to the Grizzlies. Butler was known as the Christians, but adopted the present-day Bulldogs moniker in 1919.

As for Indiana University, in the early twentieth century, their football team was known as The Crimson. Although other nicknames were used, they were short-lived and varied from season to season. A long-lasting mascot was never decided upon: In 1923, the IDS ran an article asking for the purchase of a goat to be the school’s first mascot, but this plan never came to fruition. In fact, it wasn’t until nearly two decades later when IU’s first mascot, the Hoosier Schoolmaster, inspired by a book of the same name published in 1871, was introduced in 1951.

The schoolmaster only lasted one season, and was followed by a series of similarly short lived mascots. In 1956, the Crimson Bull came to campus, followed by a bulldog named “Ox,” in 1959.

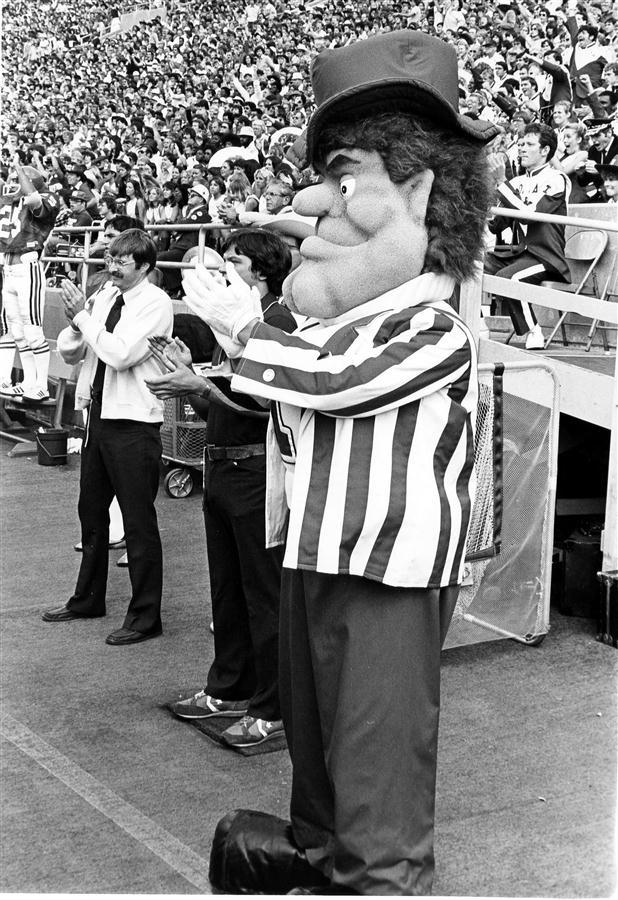

In 1965, a bison mascot was introduced. Then, in 1979, Mr. Hoosier Pride came to campus.

Instead of adopting a mascot or a distinct nickname as the other Indiana colleges did, Indiana University rallied around the word Hoosier and claimed the term for their school specifi]cally. A recently published news article states, “The word ‘Hoosier’ can refer to Indiana residents, the Indiana University sports teams or even used to describe the state of Indiana itself…” and continues, “Rohan Mathew was born and raised in Illinois, but he’s living in Bloomington as a student at Indiana University. He considers himself a Hoosier because of the values he’s gained while living in Indiana, but technically, the description might not be accurate.” Today, the historic team name The Crimson has been dropped and the replaced by Indiana Hoosiers, and the mysterious Hoosier is cited as the team’s mascot.

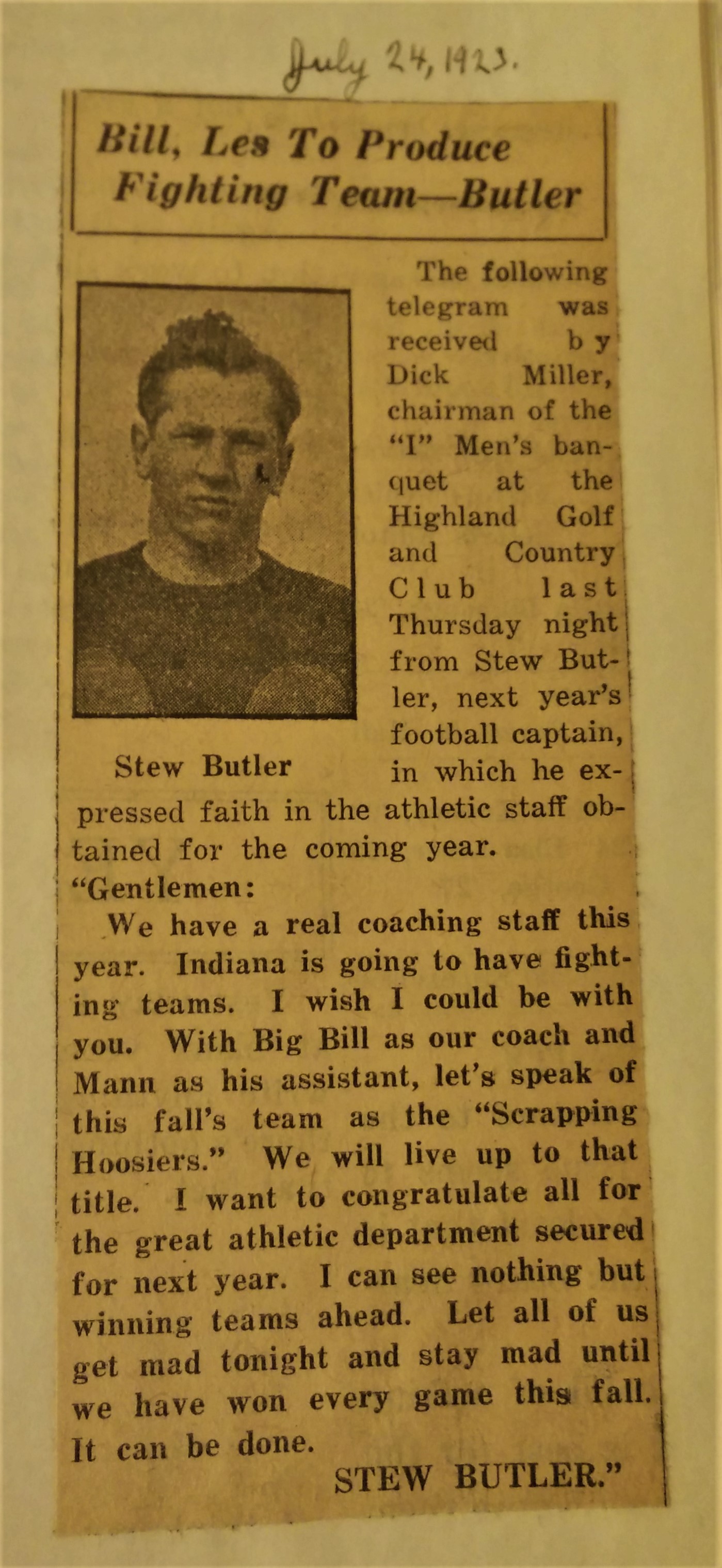

It is difficult to trace how Indiana University took a word typically used to mean, at best, hearty residents of Indiana, and, at worst, backwards, country-dwelling hicks, and applied it to students of their school specifically. The first time that Indiana University claimed the term Hoosiers for themselves even in the context of other Indiana teams was during the 1923 football season, when the team nickname became the Scrapping Hoosiers. An Indiana Daily Student article from July 24th, 1923 titled, “Bill, Les to Produce Fighting Team—Butler,” describes a telegram written by that season’s football captain, Stew Butler, to the chairman of the “I” Men’s banquet, Drew Miller, which requested that the team be referred to as the Scrapping Hoosiers for that season.

IDS articles have not been digitized after 1923, so it is difficult to continue tracing the evolution of the use of the word Hoosier after it initially became a nickname for the football team. In order to better understand the adoption of the moniker by the school after 1923, it is necessary to digitize the remaining IDS articles and create a digital map of the uses of the word Hoosier. This will allow researchers to discover patterns in when, where, and in what context the word Hoosier was used by student reporters.

From a digitized IDS database, researchers can conduct a search of the word Hoosier and codify each result. They will record the latitude and longitude of the event described so that it can be plotted on the map, as well as the date of the event so that the change over time of the words’ use can be understood. A brief description of the event taking place would also be useful, so that the information can be easily referred back to. Importantly, researchers need to code the uses of the word Hoosier, in order to understand when and where the word’s meaning changed. For example, in the early twentieth century, Hoosier was used to describe people from Indiana, cities in Indiana, characteristics of Indiana, characteristics of Indiana University, and characteristics of the countryside or backwardness.

Once the information has been coded, it will need to be converted to a KML format and uploaded into a digital mapping program such as StoryMaps or Carto. The animated map will have points representing the uses of the word Hoosier that will be different colors depending on what type of Hoosier was used. As viewers play the animation, it will chronologically show each instance of the word’s use, and display how the use changed over time.

By using a digital map to trace how the word Hoosier has been used by Indiana Daily Student reporters, researchers can better understand how the term fits into the school’s identity, and when exactly it replaced The Crimson as the team’s official name. This is important for understanding how the university created a sense of community among students and faculty, and how they maintained a connection with the state of Indiana in the face of growing national renown.

Unfortunately, coding every use of the word Hoosier proved too time consuming for the time allowted in this semester. Instead of creating a full-blown map of the places where Hoosier was used, we decided to use the Historical Newspaper Archive to count up the total of number of the times that Hoosier appears in the atabase from newspapers in Indiana. We also collected information on common phrases that are often used with Hooser.

In order to crowdsource the data, we created a Google Form which prompted people to record the number of references for every decade, so that each term we wanted to search was a different survey which people could access on their own. Google Forms transormed the survey data into a spreadsheet which we then turned into graphs

Below is the graph of the results of any use of the word Hoosier.

You can see that use of the word began to grow more steadly in the 1870s. It peaked in the 1900s and then again in the 1960s.

However, a chart of all uses of the word Hoosier does not help us answer how the usaged changed between a Hoosier from Indiana and a Hoosier from IU.In order to trace this, we used the Newspaper Archive to search for commons phrases for the word Hoosier that definently refer to IU or Indiana and again, recorded the frequency by decade into a spreadsheet. For Hoosier phrases relating to Indiana, we searched “Hoosier Club,” “Hoosier Poet,” which refers to James Whitcomb Riley, “Hoosier Athens,” refering to Crawfordsville, and “Hoosier Capital,” refering to Indianapolis. Below, you can see the graph which shows how the popularity of each term changed over time.

For words relating to IU, we searched, “Hurrying Hoosiers,” “Indiana Hoosiers,” “Fighting Hoosiers,” and “Scrapping Hoosiers.” We summed the total uses of Hoosiers which refered to Indiana and Hoosiers which refered to IU and got the following graph:

You can see that use of the Indiana Hoosier peaked between 1910-1919, just in time for Indiana’s centenential. At the same time, IU Hoosier started to be used for the first time. This is around the same time that the IDS article states that IU started calling it’s team the Scrapping Hoosiers. However, IU Hoosiers does not really start to grow until 1950. By breaking down the uses of the word Hoosier, we can see that is the time when the current team name, “Indiana Hoosiers” really took off.

The growth of the Indiana Hoosier corresponds with the rise of other Indiana college team names, which all grew steadly beginning in the 1920s.

Thus, we can see that Hoosier as a general termed gained most of its popularity around Indiana’s centennial, while IU Hoosier was spread with the growth of other college sports teams and branding. Although this method of text anaylsis was not as thorough as a digital map would be, it does provide a good basis for noticing differences in how the word has been used over time, and was much more efficient than creating a digital map. Additionally, because the method was less time consumimg, we were able to widen the scope to include all of Indiana, instead of just IDS newspapers.

Works Cited

Bakken, Dawn. “What Is a Hoosier?” Indiana Magazine of History 112, no. 3. (2016): 149-54.

Bartlett, John Russel. Dictionary of Americanisms. New York: Bartlett and Welford, 1848.

Finley, John. The Hoosier’s Nest and Other Poems. Cincinatti: Moore, Wilstach & Baldwin, 1866.

Nailos, Jennifer. “The Rise and Fall of Campus Mascots at Indiana University.” The Journal of the Indiana University Student Personal Association, (2014): 29-39.

Power, Richard Lyle. “The Hoosier As An American Folk-Type.” Indiana Magazine of History 38, no. 2, (1942): 107-122.

Vavrek, James. “What Does the Word ‘Hoosier’ Mean? Indiana Researchers Find Out,” Indiana Public Media. March 10, 2017.