An IU MicroHistory: Women’s Role in the Bloomington and National IT Workplace

Matt Hamilton, Indiana University

Overview

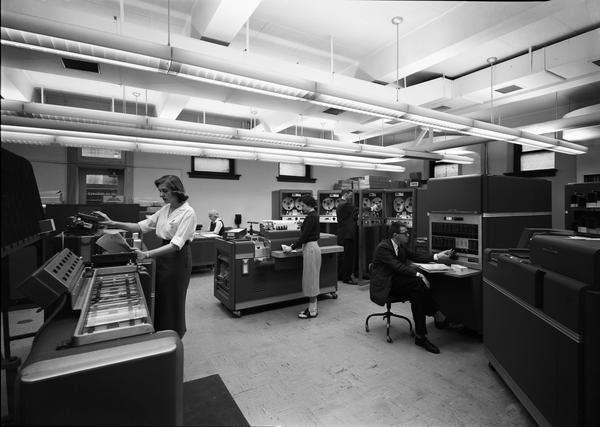

Imagine you only had a 26% chance of getting to work in a profession because of who you are when you were born (Ashcraft). This is what women going into the computing and IT fields have to contend with. Such a statistic is only one within a large swath that shows men disproportionately outnumbering women in technology-related fields in the modern age. When analyzing a primary source from Indiana University, a photograph from 1950 showing the first research computing center at IU, it’s clear that men dominating the technology-workplace has not always been the norm. Depicted are multiple women working in a large computing center alongside a couple of men. And although it’s an isolated example, the photograph still stakes the claim that there was a time when women were the primary workers with technology and operators of computers. During the Second World War, a need for women to step into increasingly technical jobs arose due to large numbers of men being away at war. In effect, women often became associated with computers and machines, and were even utilized as Vanna White -esque figures in advertisements for technology. In essence, “the women … represented a hyper-professional image of a stereotypical office worker” (Hicks). With that being said, women’s roles became less technical or intellectualized post-WWII to now, with men frequently typecast as being more technically competent than women.

Today, there stand forces at both IU and elsewhere that seek to increase women’s participation in technology-related fields. Women’s current, individualized roles in 21st technology research at IU and other universities can be heavily linked to the establishment of organizations that work to involve women in the technology sector in multimodal and interdisciplinary ways, despite there still being more men involved in those fields nationally, at IU, and at other Big Ten schools. That said, these roles can be visualized using digital tools, from which a number of conclusions can be drawn, ranging from information on regional success in integrating women in the IT field, to determining how cost of living impacts women in different states.

The Object

The photo of women working in the 1950’s IU Computing Research Center gives rise to the question: where do women have roles in the anatomy of tech fields at IU and other comparable Big Ten Universities? University data is difficult to come by, but Indiana University’s Center of Excellence for Women in Technology reports that men make up 73% of the U.S. tech field and 80% of degree-seekers in the field, demonstrating a large disparity between men and women’s interactions with technology (U.S. Department of Labor, 2015).

So seeing how, “most women opt out of the IT pipeline during their postsecondary education,” it’s not surprising to find out that women account for a significantly smaller portion of those working in or studying technology related fields, even if there have been gradual increases of women in technology at IU (Subramaniam). While IU continues to employ women in technology-related roles, the advent of groups like CEWiT is representative of the fact that women are still lagging behind. Even though women have been able to work in technology-related fields for some time now, groups like CEWiT are integral in leveraging support and empowerment for women pursuing tech careers.

Organizations

By examining how IU’s CEWiT and other university’s centers for women in technology describe themselves and their missions, their shared values and goals are brought out of the periphery. The IU CEWiT’s primary function “is to address the ‘global need to increase participation of women at all stages of their involvement in technology-related fields through research collaborations, education, mentoring, and community building… and promote women in technology and computing-related fields at IU and across the region’” (“Indiana University”). The aforementioned purpose is consistent with Indiana University’s affinity for being globally-minded, evident in the newly established School of Global and International Studies, as well as IU’s assemblage of extensive study abroad programs. Where IU is thinking internationally and locally, fellow Big Ten University, University of Wisconsin-Madison’s Women in Technology Center, is primarily focused on campus efforts. Their mission is to develop “strategies to improve the recruitment, retention and advancement of women working in IT on campus.” (“UW Women”). Focused then on staff, UW-M provides a yearly report logging any increases or decreases in percentages of full-time equivalent women compared to men working in IT titles at UW-M. Both IU’s and UW-Madison’s organizations are the result of an increased effort to filter women onto IT paths, albeit with different execution and overall goals. Nonetheless, both groups seek to increase women involvement in tech fields through multimodal means, whether it’s globally or just on campus.

Disparities

Asking why we’re beginning to focus more on increasing women’s roles in the technology sector in the 2010’s as opposed to a time like the 90’s may be different depending on who you ask, but it’s clear from national data that women’s roles in computing and IT professions from the last decade to now have decreased. Regarding the percentage of computing occupations held by women since 1990 and the percentage of female STEM undergraduate degree recipients from that time, both have decreased by over 10% to modern day (Ashcraft). Despite women no longer being considered “transitory members of the labor force,” their representation in the tech sector is miles behind men’s (McGraw). Of course, in the scheme of things, it’s also important to consider the disparity of women who are minorities to white women in the tech field. In the United States 16% of white women held computing occupations, with Asian women, Black women, and Hispanic women representing merely 5%, 3%, and 1% of the specified workforce, respectively (U.S. Department of Labor, 2015).

If there wasn’t a gap between women and men in IT fields, CEWiT and UW-WIT would probably not exist. These groups consequently stem from low numbers of women participating in the IT world. But while national statistics and demographics showing the disparity are generally known, a smaller piece of the puzzle, university demographics, are harder to come by. UW-WIT provides their own numbers showing gains in women working with technology at UW-Madison, but doesn’t publically provide numbers of women studying IT majors. Indiana University fails to do the same unless an inquiry is made. Not providing public data showing numbers of female students on IT tracks makes it difficult for analysis that allows for understanding systemic issues related to poor numbers by women in the field, especially when considering women who are minorities. Not to mention, institutional data affords the prospect of reflecting on “microinequities” as described by the National Center for Women in Technology (Ashcraft, p.22).

In a world where the U.S. Department of Labor currently projects nine out of the 10 fastest-growing jobs that needs at least a bachelor’s degree entail significant STEM training, increasing female’s opportunities in pursuing those careers are paramount in the creation of products, services, and solutions that are representative of all consumers (Hill). Making demographics regarding university progression in regards to women in tech jobs and majors easily accessible will then allow for a more transparent look at systemic policies that may impact women’s roles.

Comparing Organizations

Since the 1950 photo of women working at the Computing Research Center has propelled me to identify women’s current roles in the tech sector, I was led to organizations like IU’s CEWiT and Wisconsin’s Women in Technology Center. I’m still interested in comparing the two organizations and others in order to assist me in finding key words that help define and synthesize their goals. Through this text-mining process, I would hope to make it easier to identify common goals that could better supplement schools without similar programs to then implement their own. I understand that not all organizations would be the same, though. For example, IU CEWiT’s intention to “create a state-of-the-art, richly equipped technological ‘collaboratory’” may not be viable for a school with an endowment much smaller than IU’s (“Indiana University Bloomington”). Nonetheless, finding common goals, and uncommon ones, are key in establishing groups that can propel women forward.

Digital Component and Final Methods

By utilizing the digital mapping service, Carto.com, I was able to map universities that are listed as “Pacesetters,” a title given to businesses and colleges that “work together across corporate, startup and academic boundaries to incubate innovative ideas for broad impact” as they relate to integrating women in the workplace. I collected the data of different colleges by writing down the coordinates and names of each University listed as a Pacesetter organization and organized them in an Excel spreadsheet. I then set the spreadsheet in Carto to create a map. By analyzing the map’s data, it is clear that some states have more success than others in terms of integrating policies that promote “aggressive and measurable goals over a two-year timeframe; goals that challenge stereotypes and shape positive behaviors, improve internal processes and advance technical innovation.” (“Pacesetters”). Additionally, the east coast is the most successful region as far as having academic institutions that are Pacesetters.

The map and its data raise some interesting questions. For example, do the states with the most Pacesetter organizations have policies that support the the institution’s work in increasing women’s role in the tech workplace? Additionally, what are the goals of the individual Pacesetter organizations? The Pacesetters’ goals are kept confidential, so analysis of how each institution intends to provide women with more opportunities whether in general or in their specific setting are not possible. Nonetheless, the data produces trends that imply some regions and states having more success with promoting women to be in the technology workplace than others.

Of interest, too, is the fact that despite being the state with the second most Pacesetter universities, Indiana women earn less than the national median of women’s earnings compared to men. Indiana is in the 75-79% range, whereas the national median is 80% (“The Gender Pay Gap”). While not a poor number, I assumed that, based on the amount of Pacesetters in Indiana, women’s pay would be more on par with men’s. That is not the case. I believe this is partially due to how young some of the Pacesetter programs are. For example, IU’s CEWiT program was created in the early 2010’s, not being influential enough or having enough time to change representation or even how women in tech are perceived in Indiana. Also needing to be taken into account is how much money women and people in general receive in Indiana compared to a place like California that has slightly more Pacesetter organizations. In general, people in California receive more money because of the high cost of living. However, as more and more organizations work to better women’s role in tech, I believe that the statistics will show both higher pay for women and higher representation in the tech workplace in general, even in a place like Indiana where salaries are traditionally lower.

My Original Plan

I had originally intended to do a comparative analysis of various centers for women in technology. I would have done this by comparing each center’s vision statement and goals using the aforementioned method of text-mining to find common themes from language used. Instead, I’m ultimately making conclusions based on the mapped data from Pacesetter organizations I’ve found. This doesn’t allow me to know institutional goals or intentions, but rather analyze regional trends, uncovering policies that impact individual states and schools differently, and see stats that are then results from the policies provided.

Middle Ground

As far as a middle ground for this project goes, with help, I’d ideally be trying to acquire access to vision statements of all centers for women in technology in the United States. To add, finding out the Pacesetters’ goals would be be ideal in that it could lead to comparisions of organizations that detail the common threads that make them successful advocators for women in tech. Interviews with organization creators would also give me further perspective as to why these organizations have popped up. That way, I could compare the words that show up in each of the statements, tying them together under cohesive goals. It would help me be able to present a better argument as to why these groups have been created, in addition to arguing why they’re generally necessary in the first place. Regional frequency of these centers compared to an area’s employment data (number of women in the workplace compared to men) would be another extremely beneficial set of information as far as examining potential impacts of the centers in the region they are. Although there may not be a direct regional correlation between these centers and an areas employment, the comparison of data would allow me to, at the very least, find trends across the United States.

Conclusion

Integrating women further into the world of technology takes a significant amount of work, but organizations like IU’s CEWiT and UW-WIT are steps in the right direction. Although women may not be socialized to work with technology like they were as examined in the 1950 photograph, there are still tremendous opportunities to excel. CEWiT and UW-WIT are just two of many organizations that seek to take females in tech out of the periphery, allowing for exposure to female experts and peers that can collaborate and work so that one day women working with tech will be seen as “normal” (Dasgupta). Ideally, the number of Pacesetter organizations will also increase as a result of the positive feedback they have through their efforts to bring women into the tech sector.

References

Ashcraft, C., McLain, B., Eger, E. (2016). “WOMEN IN TECH: THE FACTS.”NCWIT 2016 UPDATE. 8-69. NCWIT. Web. 20 Mar. 2017.

Dasgupta, N., Hunsinger, M., & Scircle, M. (2014). Stereotype inoculation in adolescence: The effect of teacher gender on adolescents’ academic self-concept and beliefs about science. Unpublished manuscript, University of Massachusetts Amherst. Web. 15 Mar. 2017

Hicks, Marie. (2010). Only the Clothes Changed: Women Operators in British Computing and Advertising, 1950–1970. IEEE Annals of the History of Computing 32.4. 5-17. Web. 20 Mar. 2017.

Hill, C., Corbet, C., St. Rose, A. (1986) “Why So Few Women in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics.” AORN Journal 43.3. 1-98. Web. 15 Mar. 2017.

“Indiana University Bloomington.” IUWIT: Staff: Center of Excellence for Women in Technology (CEWiT): Indiana University Bloomington. Indiana University, n.d. Web. 05 Mar. 2017. Retrieved from http://cewit.indiana.edu/about-us/index.shtml

McGaw, J. (1982). Women and the History of American Technology. Signs, 7(4), 804. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/3173640

“Pacesetters Program.” National Center for Women & Information Technology. NCWIT, n.d. Web. 20 Apr. 2017.

“The Gender Pay Gap by State and Congressional District.” AAUW: Empowering Women Since 1881. AAUW, n.d. Web. 25 Apr. 2017.

U. S. Department of Labor. (2015). Current Population Survey. Detailed occupation by sex and race. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

“UW Women in IT (UW-WIT).” UW-Madison Information Technology. UW-Madison, n.d. Web. 15 Mar. 2017.